The History of Death in Movies

Explore death in cinema across Western film history, from silent films to today, and how it shapes audiences, culture, and filmmakers.

PHILOSOPHY

Movies have never portrayed death in only one way. Across American and Western film history, death shifts with technology, censorship, war, economics, and evolving audience expectations. Sometimes death is a staged illusion. Sometimes it is moral accounting. Sometimes it becomes spectacle. Sometimes it becomes the quiet center of grief.

This article follows a timeline approach focused on mainstream theatrical cinema, with influential ripples acknowledged near the end.

The Throughline

Across more than a century, a few structural patterns keep reappearing:

Finality vs reversibility: Does death end a story, or pause it?

Morality vs mechanics: Is death tied to ethical consequence, or treated as a functional plot tool?

Death as consequence vs death as content: Does it resolve meaning, or supply a repeatable scene type?

Communal vs individualized death: Do films frame loss as social and shared, or private and psychological?

Undead and repeatable death: When death is reversible, repeatable, or reanimated, what is the audience being trained to expect?

Those threads are the connective tissue for the timeline below.

1890s to 1920s: Death as Trick, Illusion, and Stagecraft

Early film treated death as a problem of visual representation more than an emotional event. The medium itself was new, and audiences came to the screen to see reality bent.

A landmark example is The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895), often cited for using a cut to create a convincing beheading effect. The point was not mourning. The point was astonishment at what film could “do.”

Dominant representation

Disappearances, decapitations, resurrections, and “gags”

Death framed as reversible, because the medium made it feel reversible

Narrative function

Spectacle, novelty, and visual payoff

Audience conditioning

Death is something the camera can undo

The viewer learns detachment early because the image has no permanent cost

Cultural meaning

Death as an unreal event that can be staged and controlled

Representative films

The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895)

Early trick-film traditions associated with staged illusion and substitution edits (as a dominant mode)

1920s to 1930s: Death Becomes Atmosphere, Then Morality

As film language matured, death gained weight. European expressionist cinema helped establish death as dread, shadow, plague, and fate. This mattered for Western cinema broadly because it expanded death’s emotional vocabulary beyond novelty.

In the United States, Hollywood moved toward a moralized structure that soon hardened under formal constraints.

The censorship hinge: The Hays Code

The Motion Picture Production Code (commonly “Hays Code”) shaped American studio film content from 1934 to 1968, including strong restrictions on graphic violence and other depictions.

Dominant representation

Expressionist influence: death as dread, inevitability, and environmental threat

Early Hollywood constraint: death implied, offscreen, and narratively “clean”

Narrative function

Death as moral resolution and restoration of order

Villain punishment, hero sacrifice, dignified consequence

Audience conditioning

Viewers learn to expect death to “mean something,” even when not shown

Viewers also learn that death is rarely ugly on screen

Cultural meaning

Death as justice, fate, and moral accounting

Representative films

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) as major atmosphere setters (ripples that changed the vocabulary)

The Hays Code era as the structural constraint that defines how death is framed in mainstream American cinema

1930s to 1950s: Implied Death and Narrative Order

Classical Hollywood often treated death as a decisive endpoint that restores balance. Because explicit gore was not permitted, the camera tended to keep distance while still allowing death to carry narrative weight.

This era matters because it trained audiences to associate death with:

narrative closure

moral resolution

cleanliness and restraint

Dominant representation

Implied violence and offscreen death, constrained by code-era standards

Narrative function

Ending conflict

Reinforcing a moral worldview through consequence

Audience conditioning

Death is serious, but stylized into acceptability

Grief exists, yet stories often move toward completion rather than aftermath

Cultural meaning

Death as necessary closure and social restoration

Representative films

Studio-era genres shaped by Code-era limitations (crime, war, drama) as the core mainstream training ground

1950s to Early 1960s: Cold War Scale and Impersonal Doom

The Cold War period expanded death from personal tragedy to civilizational risk. Science fiction carried anxieties about nuclear annihilation, invasion, and the fragility of human control. Death becomes systemic.

A key change occurs here: death can be everywhere, yet belong to no one in particular.

Dominant representation

Collective threat, mass death implied through catastrophe

Doom as atmosphere rather than intimate loss

Narrative function

Raising stakes to societal scale

Using death as warning and tension engine

Audience conditioning

Dread and suspense at scale

Individual deaths become less distinct when the story threatens millions

Cultural meaning

Death as existential risk and civilizational vulnerability

Representative films

Cold War sci-fi and nuclear anxiety as a defining mainstream pattern

Late 1960s to 1970s: The Break in Restraint and the Rise of Graphic Death

The collapse of the Production Code and the rise of modern ratings created a rupture in what could be shown. Films could depict death as messy, chaotic, and explicit.

Two mainstream landmarks often cited for changing American screen violence are Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Wild Bunch (1969), both associated with a new level of explicitness and a changed relationship between the viewer and violence.

Then comes a structural shift with horror.

The zombie hinge: repeatable death without moral friction

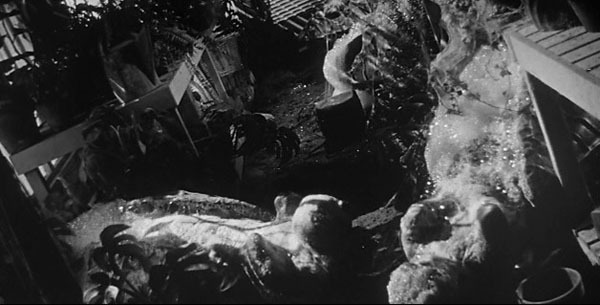

Night of the Living Dead (1968) functions in the research as a watershed for modern horror death: repetitive killing, visible corpses, and endings without moral reassurance. It also makes killing easier to accept by changing the target from “person” to “undead.”

Dominant representation

Graphic, bodily death

Death that is sudden, unredeemed, and often unresolved

Narrative function

Death as central experience, not just endpoint

The film begins to “rehearse death” through repetition, especially in horror

Audience conditioning

Higher tolerance for on-screen death through frequency and explicitness

Reduced moral friction when targets are dehumanized or reanimated

Cultural meaning

Death as chaotic reality, not polite consequence

A challenge to earlier cinematic comfort and closure

Representative films

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

1980s to 1990s: Two Death Cultures in One Multiplex

By the 1980s and 1990s, mainstream cinema holds two dominant modes at once, often separated by genre.

Mode 1: Death as metric, rhythm, and content

Action films and franchise horror normalize repeated death. The audience learns to treat death as a countable output.

The research highlights this as the era where death becomes both cheap and frequent in pop entertainment, including high body counts and dehumanized targets.

Mode 2: Death as intimate and morally serious

Prestige drama and historical film often move the other direction, treating death as final, human, and consequential.

Why the split matters

This era teaches audiences to toggle expectations:

“Is this a movie where death counts?”

“Is this a movie where death is part of the entertainment rhythm?”

That genre literacy becomes a lasting form of audience conditioning.

Representative evidence point

The research cites how 1980s action often pushed death totals into spectacle territory, with body count framed as excitement.

2000s to 2010s: The Erosion of Finality and the Grief Countercurrent

Franchise economics and cinematic universes accelerate a key trend: death becomes less final.

Death becomes negotiable

Blockbusters increasingly treat death as:

reversible via lore (magic, technology, multiverse logic)

temporary due to sequel and IP incentives

The research also notes statistical work suggesting protagonist death is comparatively rare in high-budget films, aligning with studio incentives to preserve valuable characters.

The countercurrent: death as aftermath

At the same time, grief, trauma, and memory become central subjects across drama, animation, and certain strands of horror. Here death is not the climax. The story is what continues in the living.

Audience conditioning

Modern audiences become fluent in two languages at once:

Death as reversible narrative device

Death as irreversible human reality

That tension changes how viewers interpret stakes. It also changes how creators must earn finality when they want it.

What Film Trains the Audience to Feel About Death

This section expands the strongest audience-influence claims from your research and keeps them anchored in observable viewing patterns.

Desensitization through repetition

When death is frequent, especially when victims are nameless or interchangeable, viewers adapt. Each individual death carries less impact.

Moral distancing through target design

Monsters, zombies, aliens, and faceless enemies allow killing without ethical engagement. The audience is invited to enjoy the act because the victim is framed as “not fully human.”

Expectation of reversibility

When popular characters return from death, viewers stop treating death as a stable boundary. Death becomes a pause that invites speculation instead of mourning.

Emotional outsourcing and packaged catharsis

Some films perform grief on behalf of the viewer and deliver a clean resolution arc. This can be meaningful, but it also trains an expectation that death “should” come with closure.

Normalization of violent resolution

Many genres repeatedly present killing the antagonist as the satisfying end of conflict. Over time, audiences internalize this as a normal story shape.

Cultural Meaning: What Death Comes to Represent

Your research frames several broad cultural transformations. Here they are in a cleaner, creator-friendly structure.

From mystery to mechanism

Early cinema and expressionist film frame death as fate, dread, and metaphysical boundary. Modern blockbuster logic often treats death as a solvable problem or a visual event.

From finality to interruption

Death shifts from a full stop to a semicolon. Resurrections, alternate timelines, and sequel logic train audiences to expect return.

From communal to individualized death

Mid-century cinema often frames death through collective rituals and social consequence. Contemporary films often focus on private grief, trauma, and identity reformation after loss.

From consequence to content

Death increasingly appears as a repeatable set-piece in certain genres. When death becomes a scene type, its moral and emotional weight can thin unless the storytelling actively rebuilds it.

The fading of simple morality

Code-era moral accounting gives way to:

morally ambiguous outcomes

death driven by shock, economics, or genre structure

selective seriousness where some deaths matter and others are background noise

Practical Framework for Writers and Filmmakers

These are not rules. They are diagnostic levers. They help you control what your depiction of death trains the audience to expect.

1) Finality settings

Hard finality: no return, no reversal, consequences persist

Soft finality: return is possible, but costly and limited

No finality: death is temporary or routinely undone

Ask: What does my story gain by weakening finality, and what does it lose?

2) Moral friction settings

High friction: death is ethically heavy, personal, witnessed, mourned

Medium friction: death is justified but still acknowledged

Low friction: targets are faceless, inhuman, undead, or interchangeable

Ask: Am I reducing moral friction on purpose, or by default?

3) Consequence vs content settings

Consequence-driven death: death changes the world of the story

Content-driven death: death supplies rhythm, spectacle, or genre expectation

Ask: If I removed this death, would the story collapse or simply lose a set-piece?

4) Aftermath settings

High aftermath: grief, guilt, memory, legacy, social ripples

Low aftermath: story moves on, death resolves the immediate conflict

No aftermath: death is treated as background texture

Ask: Who carries the death forward, and how?

What Cinema Has Taught Us About Death

Cinema does not teach one lesson. It teaches a shifting set of expectations.

Early film taught death as illusion and technique.

Classical Hollywood taught death as moral resolution and tidy order, with restraint shaped by code-era limits.

Cold War cinema trained audiences to imagine death at civilizational scale.

Late 1960s and 1970s cinema taught death as visible, messy, repetitive, and sometimes without redemption, with key ruptures in American screen violence and horror structure.

Franchise-era cinema trained skepticism about finality, while grief-centered films reasserted death’s human aftermath.

For creators, the enduring question is not whether to include death. It is what relationship to death the film is building in the viewer.

Influential ripples beyond the mainstream center

These are not the focus of the timeline, but they materially shaped the broader Western vocabulary of death on screen.

Art cinema that frames death as explicit philosophical confrontation, influencing later mainstream language around mortality

Animated films that introduce formative death scenes to mass audiences, often functioning as early “first contact” with loss through fiction