What is a Lich

Explore the lich myth: origins, rituals, phylacteries, strengths and weaknesses, plus why this deathless mage endures across fantasy.

PHILOSOPHY

A lich is an undead spellcaster who attains immortality through arcane means – typically by binding their soul to a hidden vessel (often called a phylactery) – thereby retaining consciousness and magical power beyond the death of their body.

Canonical Definition of a Lich

A lich is formally defined as a willfully created undead sorcerer. In fantasy literature and games, it refers to a once-living wizard or priest who deliberately used necromancy to become undead and escape mortal death.

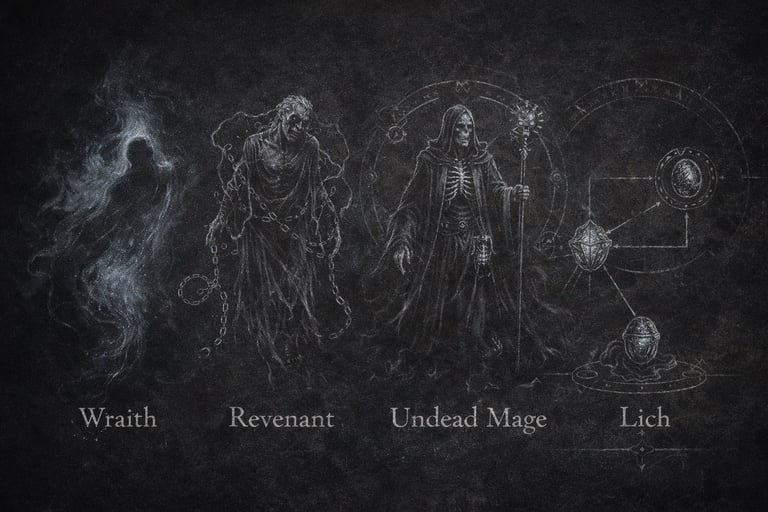

Unlike mindless undead (such as zombies or skeletons), a lich remains sapient, preserving the full intelligence, memory, and personality it had in life. Classic sources describe a lich as a gaunt, desiccated corpse-like being animated by its own soul and magic.

In essence, the lich is categorized as a sentient revenant – an undead being that chose undeath and retains its magical abilities and will, setting it apart from other undead archetypes.

Historical and Mythological Precedents

The concept of the lich has roots in myth and folklore long before modern fantasy games. Slavic folklore provides a clear precedent with the tale of Koschei the Deathless, a sorcerer who hid his soul inside nested objects (a needle inside an egg, inside a duck, inside a hare, etc.) to avoid death.

This external soul motif, Koschei could only be killed by destroying the hidden needle, is effectively an early phylactery analogy. More broadly, the motif of cheating death via magic can be traced to various legends: for example, some Middle Eastern tales and ancient Egyptian burial practices involve safeguarding life essence to attain immortality.

The term “lich” itself simply meant “corpse” in Old English (as seen in words like lich-gate for a cemetery gate) and was used in 19th–early 20th century fiction to refer to a dead body or reanimated corpse.

Early fantasy writers like Ambrose Bierce (1891) and H.P. Lovecraft (1937) employed the word “lich” in this generic sense of a corpse or possessed body, not yet as a distinct undead archetype. The modern notion of a lich as an undead mage solidified in the pulp era: authors such as Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard wrote about powerful sorcerers who returned from death through sorcery, their bodies shriveled but animated by will.

These early 20th-century stories of undying wizards (e.g. Howard’s “Skull-Face” or Smith’s necromancers) laid the groundwork for the lich concept, which was later codified by fantasy role-playing games.

Lichdom as a Deliberate Choice

Lichdom is a voluntary state – the defining feature is that the individual chooses to become undead. Unlike vampires (who often inflict their condition on victims) or revenants created by curses, a lich is formed by its own hand. The would-be lich is typically a powerful mage or cleric who decides to pursue immortality at any cost. This volitional aspect means a lich’s undeath is an active pursuit, not an accident of fate.

A common threshold in lore is that only someone with extraordinary magical skill and knowledge can even attempt lichdom, implying that ambition and intent are prerequisites. The transformation is generally depicted as an unnatural aspiration achieved through dark wisdom – the character deliberately surrenders their mortal life in exchange for an endless undeath.

The motivations for this choice are often scholarly or power-driven: liches are usually portrayed as those unsatisfied with the limits of a normal lifespan, craving unlimited time to accumulate knowledge, mastery, or influence. By becoming undead, they free themselves from biological needs and aging, dedicating every moment of endless existence to their goals.

This decision, however, is not made lightly; source material frequently notes that terrible sacrifices are required. The aspirant must knowingly forfeit their human life and morality, illustrating that lichdom’s gains (immortality and power) come at the expense of their natural life cycle. Many narratives emphasize that lichdom carries a heavy personal cost, the loss of one’s humanity or eternal damnation, underscoring that the choice, once made, is irrevocable and transforms not just the body but the very soul of the mage.

The Phylactery: Externalized Identity

Nearly every interpretation of liches highlights the phylactery as the key to their immortality. A phylactery is a container for the lich’s soul, an external object that houses the lich’s life essence, anchoring the undead existence. This mechanism is the lich’s most distinguishing feature compared to other undead.

By performing a ritual to bind their soul to a phylactery, the lich secures a form of soul insurance: as long as the phylactery remains intact, the lich cannot be permanently killed. Typically, the lich’s physical body can be destroyed, but the soul tied to the phylactery enables the lich to eventually reconstitute a new body or otherwise return, effectively rendering them immortal unless the soul vessel is also destroyed.

Liches usually take great care to hide or protect this phylactery, since it is both their source of immortality and their greatest vulnerability. The phylactery itself can be virtually any object, lore shows examples ranging from enchanted reliquaries, gemstones, or amulets, to more unassuming items, imbued with powerful magic to hold the soul.

In some works the term phylactery is used, while other fiction might call it a “soul jar” or soul gem; notably, the concept entered mainstream culture with the idea of Horcruxes in Harry Potter, which closely parallel phylacteries (objects containing fragments of the dark wizard Lord Voldemort's soul to prevent his ultimate death).

What all these variants share is the notion of externalized identity: the lich’s essence resides outside the body. Philosophically, this means the lich’s self is no longer tied to a single physical form, the true locus of the lich’s being is the phylactery. Destroying the lich’s corporeal form does not free its soul to the afterlife; instead, the soul recoils to the phylactery, waiting for a new vessel or the means to reform.

Only if the phylactery is itself destroyed is the lich’s soul finally rendered vulnerable to permanent death, at which point slaying the lich’s body has lasting effect. In summary, the phylactery is the linchpin of lichdom, it is both the source of a lich’s immortality and an Achilles’ heel that defines the creature’s existence.

The Ritual of Lichdom

Becoming a lich is not an accidental occurrence but the result of a deliberate magical ritual.

In lore, would-be liches undergo a secretive and perilous transformation ritual engineered to sever their soul from their living flesh and bind it into the prepared phylactery. The specifics of the ritual vary by source, but it invariably involves dark necromantic magic and often rare or horrific reagents.

One classic depiction in Dungeon & Dragon's lore is that the aspirant must brew and consume a potion of transformation (sometimes called the “elixir of lichdom”), laced with poisonous or occult ingredients, which causes their mortal death while the soul is captured in the phylactery. Another description portrays an incantation or spell that kills the caster outright as a sacrifice, immediately raising them as an undead and transferring their soul to the vessel.

In all cases, the ritual is an intentional self-killing: the mage effectively orchestrates their own death at the climactic moment, trusting that the dark magic will reanimate them as a lich rather than let them die permanently. This process is fraught with danger. Sources note that if any step of the ritual fails, if the phylactery isn’t properly prepared, or the incantation is imperfect, the aspirant simply dies like any other mortal.

Thus, lich lore often speaks of these rituals being done under auspicious conditions (astronomical alignments, rare celestial events) to ensure success. The transformation is usually depicted as excruciating and tainted, not a flashy spectacle but a grim, methodical procedure that the caster endures knowingly.

Importantly, lichdom isn’t achieved once and then forgotten, some continuities describe ongoing dark practices after the initial transformation. For example, a newly created lich may need to perform periodic rituals or sacrifices to maintain its undead state or to bolster its power, essentially reaffirming the lich’s condition over time.

In summary, the ritual of lichdom is treated as an arcane, esoteric process: an engineered path to undeath that requires meticulous preparation, profound knowledge of necromancy, and a willingness to pay utterly extreme costs (including one’s own life) to complete.

The Nature of Lich Undeath

Once the transformation is complete, a lich exists in a state of undeath fundamentally different from a living being.

Physically

A lich’s form is corporeal but necrotic, typically a withered, mummified or skeletal body that shows clear evidence of death and decay (in contrast to, say, a vampire who may appear alive). The flesh (if any remains) is desiccated on the bones, and often only sunken skin or even just a skeleton remains; in many depictions the lich’s eye sockets glow with unnatural light, emphasizing the animating magic within.

Despite this corpse-like appearance, a lich’s body is preserved by sorcery and does not decompose into dust so long as its soul-infused phylactery sustains it.

Biologically

The lich is inert, it no longer ages, breathes, eats, or sleeps. Freed from these living processes, liches are often said to be “unburdened by bodily needs,” allowing them to spend centuries in uninterrupted study or planning. They are immune to disease and to ailments of the living; their existence is maintained by magical energy rather than any metabolism.

Mind and Personality

A lich remains the same person (for good or ill) that it was in life, albeit often greatly changed by the passage of time and the effects of undeath. Crucially, liches retain full self-awareness, memories, and intellect, unlike lesser undead. The sapience and often the specific expertise (magical knowledge, strategic cunning) of the individual are intact after the transformation.

Many lich characters continue pursuits they had in life, for instance, if a wizard became a lich to continue researching magic, they will persist in that research with undiminished intellect (potentially even enhanced by having centuries to study).

However, undeath can also alter one’s psyche. Separated from mortal sensations and society, liches often develop an alien, detached perspective. They may become pathologically obsessive, exceedingly patient, or coldly logical, as human emotions dull over centuries of unchanging existence.

Some lore suggests that a lich’s soul, by being tethered to undeath, might lose the capacity for empathy or joy. Early accounts like Bierce’s note that a risen corpse “hath no natural affection… but only hate”, implying a loss of humane traits in undead existence. While this is not a strict rule (a lich’s personality could theoretically be kind or noble if it was so in life), most fiction depicts liches as inhumanly cold or evil, a likely side effect of the dark path they’ve taken.

Additionally, the magical nature of a lich’s being grants it supernatural traits: liches often radiate a kind of aura of dread or darkness and exert a palpable presence of death. They do not tire, and mundane physical injuries may not slow them (their bones can be magically reinforced, and lacking flesh means no pain or bleeding in the human sense).

In some settings, a lich’s body can gradually deteriorate further if its magic wanes, for example, neglecting to maintain its power might cause a lich to crumble into a demilich, essentially a vestige like a skull with only faint consciousness remaining. But a fully empowered lich is essentially a walking corpse imbued with arcane force, as agile or strong as it animates itself to be, and often protected by spells.

In summary, the nature of lich undeath is that of a being who is physically dead but magically alive: it has cast off the rhythms of life to exist in an unnaturally static state, with a mind that endures forever and a body that persists through sorcery rather than biology.

Power, Limits, and Costs

Liches are invariably portrayed as formidable beings, but their power is balanced by specific limitations and the costly upkeep of their immortality.

In terms of raw power, a lich is often mightier in undeath than it was in life, freed from mortal frailty and having indefinite time to hone its craft, a lich can accumulate vast magical might. Many liches command hordes of lesser undead; they act as generals or overlords of undead armies, using skeletons, zombies, wights, and other minions as extensions of their will.

They typically also possess potent personal abilities: as former high-level spellcasters, liches wield a wide array of spells (often with unique ones they devised over centuries) and innate powers such as life-draining touch, fear auras, or other necromantic effects. In short, a single lich can be an arcane threat equivalent to an entire company of lesser foes, which is why they frequently occupy the role of endgame villains or legendary figures in stories.

However, lichdom does not confer invulnerability. Perhaps the most significant limitation is the dependency on the phylactery: the lich’s immortality is tied to that item, so if the phylactery is discovered and destroyed, the lich becomes as killable as any mortal. Even before that extreme, destroying a lich’s physical form is a setback, the creature typically needs time (and often dark rituals) to reconstitute a body near its phylactery.

During that interregnum, the lich is effectively neutralized, so being forced out of corporeal form can derail its immediate plans. Moreover, many settings impose that liches must actively maintain their undeath. For example, Dungeons & Dragons lore specifies that a lich must periodically feed souls to its phylactery to keep the magic intact; if it fails to do so, its body will begin to decay and eventually crumble into a lesser form (the demilich) or cease entirely.

This creates a continuous cost to immortality: the lich must commit ongoing atrocities (soul sacrifices) just to remain undead, highlighting that its power demands constant renewal. Even aside from such specifics, the magical energy sustaining a lich can wane, a complacent lich that doesn’t rejuvenate itself might find its physical form degrading over the centuries.

Liches also share common undead vulnerabilities. They are typically susceptible to powerful holy or sacred magic; in many stories, prayers, divine rituals, or relics can weaken or ward off a lich. They usually cannot tolerate consecrated ground or certain symbols of life (for instance, some lore suggests a “symbol of true life” can prevent a lich from reforming, effectively trapping it in demise).

Additionally, while a lich’s undead body is durable, it can be physically destroyed by sufficient force or magic, forcing the lich into spirit form. This means that in combat, liches often avoid direct physical confrontation, preferring to fight indirectly via minions and spells, they know that losing their body, even temporarily, is inconvenient and potentially dangerous if their phylactery were to be found in the interim.

The psychological and spiritual costs of lichdom are also emphasized in many narratives. The transformation process itself is profoundly evil or unnatural in most settings, often requiring heinous acts (such as murdering innocents to fuel the ritual). As a result, a lich often bears a curse of corruption.

For example, it may be tormented by its separation from the cycle of life, or suffer an eternity of loneliness and fixation. Characters who pursue lichdom “often pay heavy costs (loss of humanity, eternal torment), underscoring a theme that endless life without change can be its own torment”.

Thus, far from being a blissful eternal life, lichdom is frequently depicted as power at a steep price: the lich achieves unending existence and knowledge, but experiences existence in a grim, unliving state devoid of the joys of life. Some works even frame lichdom as a trap. The lich gets endless time but also an endless, possibly empty, existence. Sometimes liches in fiction eventually regret their immortality, finding it hollow, though pride or fear prevents them from relinquishing it.

Lastly, even the power liches wield has its pragmatic limits. They may be immortal, but they are not omnipotent. Liches can be outwitted, magically contained, or temporally defeated by heroes. And crucially, if a concerted effort is made to locate and destroy the phylactery, a lich can be permanently slain just like any mortal enemy. Indeed, in most fantasy narratives, this is the only sure way to get rid of a lich.

This vulnerability means liches must often act cautiously and in the shadows, guarding the secret of their phylactery’s location. In summary, a lich’s profile is that of immense strengths balanced by singular weaknesses: they wield great and lasting power, but their immortality is tethered to an object and a dark upkeep, and the very process that makes them powerful also exacts profound costs on their being.

Liches as Long-Term Systems

Liches are not just individual monsters; they function as long-term actors and systems in their worlds. Thanks to immortality, a lich can influence events across centuries or millennia, making it less a transient foe and more an enduring fixture of history.

Patience and foresight become the lich’s greatest weapons. Unlike mortal beings that have limited lifespans, a lich can afford to execute plans over decades or wait for specific epochs to align. It will often scheme in multi-generational timelines, knowing it can simply outlive its opponents. Canonical lore from Dungeons & Dragons notes that a lich will pursue its goals “patiently and single-mindedly,” often preferring to outlast enemies rather than confront them directly. They might withdraw for 50 or 100 years, let kingdoms rise and fall, and then emerge when conditions are favorable, essentially playing the long game in any conflict.

This makes a lich a structural presence in a fantasy setting: it might be the unseen hand that has guided a secret society for centuries, or a dormant threat that recurs every few hundred years when some seal weakens. Many liches establish strongholds or domains where they can operate in relative seclusion for long periods. They tend to lair in remote, often inaccessible places like ancient tombs, abandoned cities, hidden libraries, or other fortified sanctums to avoid constant disturbance while they work on their millennium-spanning schemes.

Within these lairs, a lich often accumulates vast resources: over time it collects arcane tomes, artifacts, and tools, effectively becoming a living archive of knowledge and magic. Some liches even become linchpins of larger systems, such as ruling an undead-controlled region or serving as the secret advisor to mortal rulers across generations (using disguise or proxies). The “long-term system” view also means liches can be world-builders.

In some settings, the presence of a lich shapes entire societies or eras. For example, in the Forgotten Realms (a D&D world), there are liches like Szass Tam who rule Thay, a magocratic nation for centuries, entrenching undead governance as a system. In Warhammer Fantasy, the arch-lich Nagash is said to have caused the fall of ancient civilizations and ushered in the Age of Undeath, essentially attempting to remake the world in undeath’s image.

These are cases where a lich’s personal existence scales up to a civilizational scale. Even a solitary lich in a dungeon can be treated as a long-term influence: it might be the ancient source of a magical curse plaguing the land, or the keeper of lore from a bygone age that protagonists seek. Because liches do not die naturally, they serve as bridges between eras.

A lich might remember firsthand the events of a distant age, making it a living witness or relic of history that contemporary characters find daunting or invaluable. In interactive media, like strategy or role-playing games, liches often act as renewable adversaries: if not utterly defeated (phylactery and all), they can return after defeat, providing a persistent challenge. This longevity means a lich can evolve over a narrative as well, potentially accumulating new powers or shifting tactics after each revival, almost like a self-updating system.

In summary, liches function as long-span entities in fiction, they are built for the long term, with narratives often emphasizing their virtually unlimited time horizon. They turn into far-reaching systems: guarding knowledge eternally, manipulating events from the shadows, and surviving where any mortal institution would crumble. This makes them qualitatively different from mortal antagonists; a lich is less a person and more an institution unto itself, one that can span multiple story arcs or historical epochs within a setting.

Liches Across Media and Genres

Since their popularization in 20th-century fantasy, liches have appeared across a wide range of media, though specific portrayals vary, the core concept remains recognizable.

Tabletop role-playing games established the archetype: in Dungeons & Dragons (1970s onward), the lich is a staple high-level monster, explicitly defined as a spellcaster who seeks to defy death by magical means. Many subsequent RPGs adopted this model. For instance, Pathfinder, 13th Age, and other D&D-inspired games include liches with similar phylactery mechanics.

Warhammer Fantasy’s lore introduces Nagash as “the first liche,” essentially injecting the lich archetype into that universe’s deep history as an origin of necromancy. Video games often feature liches as well, sometimes as major bosses and sometimes as common undead enemies (though not always with full narrative).

The Might and Magic series and its strategy spin-off Heroes of Might and Magic make heavy use of liches. In those games, liches are units or heroes in undead factions, depicted as skeletal sorcerers wielding death magic. One notable character is Sandro from Heroes of Might and Magic, a recurring undead wizard who exemplifies a lich scheming across multiple games.

In Blizzard’s Warcraft universe, liches also appear prominently: the character Archlich Kel’Thuzad is a classic lich, a former mage who was resurrected as an undead spellcaster bound to a phylactery, and the infamous Lich King is the title of the ruler of the undead Scourge, though the Lich King is a unique fusion of entities, the concept ties closely to lich lore. The Wrath of the Lich King expansion of World of Warcraft centers on this character, underscoring how the lich motif as an undead overlord commanding armies of undead has broad appeal.

Other games have playable lich options or lich-themed storylines. For example, Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous (CRPG) allows the player to pursue lichdom, and games like Dark Souls or Elden Ring include lich-like sorcerers who achieved undeath for power though not always labeled “lich”.

Literature and film occasionally use the lich archetype under other names. A famous example is Lord Voldemort from the Harry Potter series: while not called a lich, he preserves his soul in Horcruxes (soul fragments in objects) exactly as a lich does with phylacteries, which is why he returns after death until those anchors are destroyed. Voldemort’s case has often been compared to a lich by genre fans, as it illustrates the same concept of a dark wizard achieving quasi-immortality through soul vessels.

Earlier fantasy novels and stories sometimes had lich characters as well. For instance, Fritz Leiber’s “Thieves’ House” (1943) featured a jeweled skull guarding treasure, a concept that later influenced D&D’s demiliches. In contemporary fantasy fiction, the term “lich” might be used or just the concept employed (e.g. a necromancer prolonging life via a spirit jar).

Comics and web series also embrace liches: the webcomic The Order of the Stick famously has a lich villain (Xykon) who plays with and subverts many D&D lich tropes. In the realm of animation, an iconic example is Adventure Time’s character The Lich, a transcendent undead entity and personification of death that the protagonists confront. This character is simply called “The Lich” and embodies pure evil and entropy, a more cosmic horror take on the concept, but still essentially an ancient sorcerer who became an undying embodiment of destruction.

Across these media, details can differ. Some portrayals drop the phylactery aspect for simplicity, a video game might label a skeletal mage enemy as a “lich” even if it doesn’t exhibit immortality in gameplay. Others explore unique twists, a few settings have good-aligned liches like D&D’s archlich or baelnorn, undead sages who voluntarily guard their people or knowledge beyond death, showing that lichdom isn’t inherently evil.

Alignment and personality can thus vary: while the archetypal lich is an evil, power-hungry villain, some stories allow for liches that are aloof but not malevolent e.g. a neutral caretaker of a library who chose undeath to protect knowledge eternally. The consistent thread, however, is the notion of a necromantic immortality.

Whether in a novel, game, or film, if you encounter an undead magic-user preserving itself via some talisman or dark ritual, you’re likely dealing with a variation of the lich trope. The term “lich” itself has become widely recognized in fantasy gaming and literature, to the point that it’s regularly used in titles and descriptions as shorthand for this type of character.

This cross-media presence speaks to how ingrained the lich is in the fantasy genre’s vocabulary from D&D sourcebooks to MMORPGs and young adult novels, the lich’s image as a skeletal mage clutching a spellbook, often with a glowing phylactery nearby is instantly identifiable. Each new work might put a spin on it, but they all contribute to the same enduring legend of the lich.

Common Misconceptions About Liches

Liches are complex creatures in lore, and several common misconceptions have arisen that are worth clarifying:

Any undead wizard is a lich

Not necessarily. A common mistake is to label any magically inclined undead as a lich. In truth, lich refers to a very specific process and state: a sorcerer who intentionally became undead via a soul-phylactery ritual. Many undead mages in fiction e.g. a wraith-like necromancer or a resurrected skeleton mage are not true liches unless they have that soul-anchor and self-directed immortality. The defining feature is the phylactery-bound soul; without it, an undead spellcaster is mortal and lacks the lich’s regenerative immortality, and would be classified differently.

Destroying a lich’s body destroys the lich

False. A very common misconception is that slaying a lich’s skeletal body is the end of it. In most lore, killing a lich’s physical form is only a temporary victory. Unless its phylactery is also destroyed, the lich’s soul remains tethered to the world and will eventually restore a new body. Adventurers who don’t realize this might be shocked when the supposedly vanquished lich returns. The proper way to permanently destroy a lich is to find and eliminate its phylactery thus releasing or extinguishing its soul before or in addition to defeating its corporeal form. This nuance is central to lich lore and separates them from typical one-and-done villains.

Liches are invulnerable immortals

Not exactly. While liches are indeed ageless and hard to kill, they are not invincible. Their immortality is conditional: they must safeguard their phylactery and, in many depictions, maintain their undeath through magical means.

For example, D&D lore explicitly states a lich must feed souls to its phylactery periodically to prevent decay. If they neglect this, they can physically deteriorate or even cease to exist. Additionally, liches can be defeated or contained by powerful magic, holy intervention, or clever tactics, they have weaknesses (such as vulnerability of the phylactery, susceptibility to specific spells or artifacts, etc.).

Thus, liches have longevity and resilience, but they do pay costs and face risks to sustain it (their immortality is “perverse” and requires constant dark upkeep, not a carefree eternal life).

All liches are evil

Not universally.

The trope of the lich is usually tied to nefarious characters (indeed, most are depicted as wicked tyrants or mad wizards), but it’s a misconception to think that any lich must be evil by definition. Some fantasy settings acknowledge benign or neutral liches: for instance, in the Forgotten Realms, there are good-aligned liches (sometimes called archliches or baelnorn) who underwent the lich ritual for altruistic reasons such as protecting a family’s knowledge or serving as an eternal guardian for a community.

These cases are rarer, but they demonstrate that lichdom itself is a tool; the morality depends on the user. That said, even “good” liches tend to be eerie and imposing, and may use undead minions, so to outside observers they can appear just as frightful. The key point is that while the process of lichdom is dark, an individual lich’s goals need not always be world domination or cruelty (though in the vast majority of stories, evil is indeed the driving force).

Lichdom is like a disease you catch (or a curse given by another)

Incorrect.

Unlike vampirism or lycanthropy, lichdom is not an infection or curse that can be passed to an unwilling victim. It cannot happen by accident or mere exposure. Becoming a lich is a personal endeavor, a result of one’s own studies and rituals. One lich cannot simply “turn” someone else into a lich by biting or spellcasting in most canonical lore.

A lich might teach or coerce someone into performing the ritual on themselves, but the person must actively go through the process. This happened to Malin Keshar in the Descent into Darkness campaign of Battle for Wesnoth. Darken Volk offers Malin a way to protect his homeland through the use of Necromancy later convincing the young Malin to turn to lichdom.

This means you won’t randomly become a lich; it’s an opt-in transformation. The misconception otherwise likely comes from conflating liches with other undead who do propagate their condition. In summary, lichdom is a chosen and engineered state, not a contagious undead curse.

“Lich” is a term exclusive to one franchise or game

No. Sometimes newcomers assume “lich” is a Dungeons & Dragons-only idea or specific to one story. In fact, lich has become a generic fantasy term used across many worlds and franchises to denote this archetype of undead sorcerer. D&D popularized it, but today one finds liches in countless independent novels, games, and myths.

The concept has even been renamed in some contexts (e.g. “Deathless” or “Undying”), but these are essentially the same idea under another label. The broad adoption of the term can lead to inconsistent details (each universe sets its own rules for liches), which is why understanding the core definition (soul anchored undead mage) helps clarify what is and isn’t a lich in any given work.

By dispelling these misconceptions, we see the lich more clearly: not as an all-powerful invulnerable ghoul or a generic skeleton mage, but as a very specific type of undead mastermind with defined strengths, weaknesses, and narrative rules.

Why Liches Persist in Fantasy

The lich endures as a popular figure in fantasy because it resonates with some of the genre’s most enduring themes and fears. Fundamentally, liches symbolize the ultimate human ambition, to conquer death, taken to a macabre extreme.

This makes them fascinating antagonists and characters: they explore the question, “What if mortality could be defeated through will and sorcery, and at what cost?” Many cultures have myths of immortality quests, and the lich is the personification of that quest fulfilled in the darkest way. This intrinsic connection to the mortality theme means liches remain relevant as long as stories grapple with life, death, and the desire to escape death.

From a storytelling perspective, liches serve a unique role. They combine qualities that create a compelling villain or anti-hero: immense wisdom and intelligence unlike bestial undead, a personal backstory of hubris, and the horrifying aspect of undeath. A well-crafted lich has depth, it was once a person, often a great one, and its current form reflects an internal transformation (pride, fear, obsession) as much as an external one.

This allows writers and game designers to use liches for rich narrative arcs, not just as mindless monsters to defeat. A lich can have ancient grudges, extensive knowledge of the world, and long-laid plans, which makes the conflict with them more intricate and weighty.

In gaming terms, liches persist because they provide a memorable endgame challenge that fits high-level fantasy. They are the archetypal “arch-villain in the tower of sorcery” – an enemy that justifies the heroes’ growth and stands as an ultimate test of wits and strength. The presence of a lich immediately raises the stakes in a story: dealing with someone who has cheated time and death implies epic consequences.

Liches also offer a measure of continuity and franchise identity. In D&D and its descendants, for example, certain named liches like Vecna or Acererak became iconic villains referenced across editions and adaptations. These characters persist in the lore sometimes literally resurrecting within the story, which in turn cements the lich’s place in the fantasy canon.

Even outside of those franchises, new works often reinvent the lich concept, the idea of a deathless sorcerer shows up in everything from anime to card games, demonstrating its versatility and appeal. Conceptually, the lich persists because it’s a dark mirror to heroes and to humanity. It answers the question: What if one’s drive for knowledge or power eclipsed every moral and natural law?

In that sense, a lich is the embodiment of unchecked ambition as a cautionary tale that achieving god-like life might strip away one’s humanity. These themes are evergreen in literature. There’s also an aspect of moral complexity that keeps liches interesting.

Unlike a mindless zombie horde which might symbolize unreasoning death or plague, a lich is choosing to be what it is. It is a sentient villain with often rational, if extreme, motives, which can sometimes even be sympathetic or at least understandable e.g., a lich who sought eternity simply out of fear of the unknown death. This allows explorations of villainy that are nuanced; a lich can be a tragic figure in some tellings or an utterly reprehensible tyrant in others.

In both cases, the audience is confronted with the idea of desiring life too much or the corrupting influence of absolute power. Culturally, the lich’s persistence is also reinforced by the broad diffusion of the trope in media. Audiences have encountered liches in many media forms and find them intriguingly familiar yet flexible. They are part of the established fantasy lexicon alongside dragons, elves, and vampires.

Each new story that features a lich builds on the collective archetype while adding a new twist, thereby renewing interest. In summary, liches persist in fantasy because they hit a storytelling sweet spot: they are intellectually engaging, thematically rich, and dramatically formidable.

They personify timeless fascinations, immortality, knowledge, control, and fears, corruption, death, the undead, all in one figure. As long as fantasy fiction continues to explore the line between life and death, and the consequences of power, the lich will remain a potent and reusable symbol in that narrative landscape.

Liches as a Model of Control

Analyzed from a systems perspective, the lich can be seen as an extreme model of control over self, over death, and over others. At the core, a would-be lich refuses to cede control to the natural order (i.e. to mortality).

The lich’s entire existence is an assertion of willpower over fate: rather than allowing death to occur, the lich takes control of the boundary between life and death, bending it to their design. In doing so, the lich establishes an unprecedented level of self-determination, they have literally mastered their own mortality through magic. This makes the lich a symbol of ultimate autonomy: it answers to no natural law, only to its own sustained will and the magical framework it set up to enable that will.

Liches also seek control externally. By their nature (often as former tyrants, wizards, or kings), many liches desire to impose order or dominion on the world around them, in line with their goals. Having extended their influence across time, they often extend it across space by subjugating others hence the common image of a lich ruling an undead legion or domineering a region through fear and sorcery.

In narratives like Warhammer’s Nagash, this is taken to a grand scale: Nagash aspired to an “age of Undeath that will bring order and peace for all eternity,” essentially remaking the world under his total control seeing the silence of undeath as “order and peace”. This is a prime example of a lich’s mentality of control: even positive concepts like peace are twisted into something achievable only by absolute domination; in his case, killing all life and ruling over the dead.

The lich’s immortality also means control over time, they can wait out any opponent or obstacle, as discussed, which gives them a strategic advantage. They can manipulate events from afar, pulling strings over generations, control over history itself, in a sense.

In many stories, a lich carefully orchestrates events by controlling information being an undying schemer, it might seed prophecies, hoard knowledge so others cannot use it, or puppeteer mortal agents through promises of power or threats.

Furthermore, liches often meticulously control their own environment. Their lairs are filled with wards, traps, and enchantments to ensure nothing happens within their domain without their consent. They typically have contingency spells for escape, regeneration, or revenge, reflecting a highly controlled approach to any contingency, a “plan for everything” mindset.

Even their reliance on undead servants is telling: undead are unthinking or obedient, far easier to control than living minions with free will. A lich often prefers an army of skeletons that will mindlessly follow commands to an army of humans that might betray or err.

Philosophically, the lich represents the idea of absolute control versus the chaos of life. By eliminating their own life, they eliminate unpredictability within themselves, no aging, no sickness, no emotional whims from hormones or physical needs. By surrounding themselves with death, they attempt to create a static, controlled reality. In this way, a lich’s domain is like a rigid system meaning that everything is ordered, lifeless, and within the bounds the lich has set.

This can be viewed as a dark reflection of a utopian impulse: many lich stories show that the lich believes the world would be better if they controlled it since they often see themselves as uniquely enlightened or deserving, which is why some liches have almost doctrinal visions of establishing eternal kingdoms. The cost, of course, is the elimination of freedom, both others’ and ultimately their own, as they often become a slave to their phylactery and obsessions.

In analytical terms, the lich is an actor that optimizes for permanence and control at all costs. It sacrifices the mutable, organic, and uncertain (life, change, relationships) in favor of the fixed, predictable, and secure. Many liches are depicted as incapable of adapting to truly new paradigms (they are literally “old school” and can be blindsided by creative chaos or love or anything not in their controlled calculations).

Still, within the contexts they operate, they are masters of setting the rules. From a meta-fictional perspective, one can even see the lich as an embodiment of an authorial figure within the story: just as authors control narratives, a lich tries to script reality to its will, often knowing the “lore” of the world intimately. They often literally write prophecies or books that shape societies.

Observing a lich thus provides commentary on control itself, it asks, what is the end-state of needing to control everything? Invariably, fantasy answers that with a grim picture: a world of death and stasis. That is why liches are almost always eventually opposed by heroes who carry the messy vitality of life.

In conclusion, liches epitomize control without balance. They control death, they create oppressive order, and they tightly manage their surroundings. This makes them fearsome, but it also often sows the seeds of their downfall.

As models of control, liches illustrate the ultimate anti-thesis of the natural cycle – a system where all variables are locked down except the lich’s will, maintained indefinitely. This is both their strength and their fatal flaw in the grander scheme of fantasy narratives.

Final Synthesis

The lich stands as one of fantasy’s most definitive explorations of undeath and ambition. It is a construct of will, magic, and intellect that has moved through myth, literature, and games, accumulating layers of meaning yet remaining fundamentally recognizable.

At its heart, the lich is the answer to a question that humans have asked for ages: what if death could be beaten through knowledge? The answer, in the lich’s case, is both awe-inspiring and terrifying. By converting a living self into an undead existence, the lich trades the ephemeral nature of life for the permanence of unlife – achieving a goal as old as myth, but in a way that reflects humanity’s deepest fears about what one might become in the process.

This duality, triumph over death at the cost of one’s humanity, gives the lich a lasting presence in our stories. It has evolved from archaic folklore of soul jars and deathless sorcerers into a modern archetype, but it hasn’t lost its relevance.

On the contrary, each new depiction reaffirms the lich’s place in the imaginative landscape, much like the lich itself returning time and again so long as its phylactery survives. In a sense, the lich as an idea is immortal: it adapts, reappears, and persists across creative works. Just as a lich in lore might survive the ages, the concept of the lich endures across generations of fantasy, an undying reminder of the price of defying the natural order.

Through a neutral lens, the lich can be viewed as neither hero nor simple villain, but as a phenomenon; a convergence of themes about control, knowledge, and the unnatural extension of existence. Its story is rarely told with finality; often, a defeated lich in a narrative leaves behind its phylactery, hinting that it will rise again.

Likewise, in the grand tapestry of fantasy fiction, the lich recurs whenever we delve into the notion of power that outlasts death. In the end, a lich is not just a monster in a dungeon or a dark lord in a ruin, it is a repository of memory and will, an object lesson in the ultimate pursuit of control, and a fixture of mythic imagination that continues to hover between life and death, indefinitely, in the pages of our stories and the code of our games.